- The dismal performance of emerging market equities during the past three years (a total of -20%) suggests that a rebound may lie around the corner.

- Yet, country-specific factors aside, three key global factors argue otherwise: 1) insufficiently attractive EM valuations, 2) the structural deterioration in EM balance sheets and the resulting vulnerability to 3) tightening global monetary conditions.

- The latter in particular far surpasses the small 25bps hike the Fed delivered in December 2015. The end of QE3 is estimated to be equivalent to a 300bps tightening, while the sharp decline in foreign holdings of US Treasury securities further adds to a vicious cycle of tightening monetary conditions.

- In the short term, rising commodity prices provide non-trivial support to EM assets, but the persistent structural economic weakness and the risk of a shock to market expectations of Fed hikes implies that investors should fade rallies, rather than buy into them.

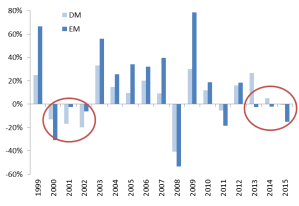

Emerging market equities have had a tumultuous start of the year. While the EM MSCI rose about 5.7% in Q1, this belies a very volatile period, marked by a 13% decline until mid-January, followed by a 21% rise since (in USD terms). What is more, this came on the heels of a 15% decline in 2015 and was preceded by another two years o f losses, for a cumulative total return loss of 20%. Worse yet, four of the last five years posted a negative return. The last time EM equities declined for three consecutive years was more than a decade ago, in 2000 to 2002, when the cumulative loss amounted to 45%. At that time, this was followed by five years of double-digit gains. It is tempting to think that markets are now at a similar juncture and that this could be the time to buy.

f losses, for a cumulative total return loss of 20%. Worse yet, four of the last five years posted a negative return. The last time EM equities declined for three consecutive years was more than a decade ago, in 2000 to 2002, when the cumulative loss amounted to 45%. At that time, this was followed by five years of double-digit gains. It is tempting to think that markets are now at a similar juncture and that this could be the time to buy.

There are three powerful reasons why this is unlikely (country-specific factors aside). They relate to valuation, balance sheets and monetary conditions.

Insufficiently Attractive Valuations: Nominal valuations have indeed corrected significantly. The MSCI EM index level has fallen from 1100 in September 2014 (1170 in 2011) to below 700 by late January (837 currently). In relation to earnings, P/Es had reached a peak of 15.4 in April 2015, from which they declined to below 11.0 in January 2016 (before rebounding to 13.1 by end-March). However, it is important to consider the market’s P/E not only relative to its own history, but also in the context of other markets and risk assets. Most notably, EM P/Es typically trade almost 20% below DM P/Es (15- year average). The discount had fallen as low as 25%, similar to the discount in mid-2014 or in 2008. But this was nowhere near the 40-60% discount range witnessed in 2001-03 before the double-digit take-off. What is more, the discount has now rebounded to above its long term average, into the mid-teens. From this perspective then, a repeat of the double-digit growth rate episode experienced from 2003 is not warranted.

year average). The discount had fallen as low as 25%, similar to the discount in mid-2014 or in 2008. But this was nowhere near the 40-60% discount range witnessed in 2001-03 before the double-digit take-off. What is more, the discount has now rebounded to above its long term average, into the mid-teens. From this perspective then, a repeat of the double-digit growth rate episode experienced from 2003 is not warranted.

Balance Sheet Deterioration: It is well appreciated that emerging markets have experienced a secular growth slowdown as their out-performance over developed markets declined from a peak of some 7% in 2011 to just over 2% in 2015. Given the productivity slowdown this went in hand with, it is clear that the aberration is not so much the current situation, but rather the period of accelerating growth between 2004 and 2012 when EM economies were fueled by rising commodity prices and increasing liquidity provision by G3 central banks.

A less widely appreciated fact is the successive balance sheet deterioration of emerging markets since the start of this decade. While there has been ample focus on the cyclical worsening of current account-and fiscal flows (partly related to lower commodity prices, partly to lower growth), there has been less recognition of the structural balance sheet deterioration which resulted from this succession of deficits. On the  one hand, broad credit to the private sector in EM has increased from 70% of GDP in 2000 to 130% of GDP in 2015 (87% ex-China). Of this, about 20% of GDP represent external debt. On the other hand, EM foreign reserve growth slowed since 2011 and went into sharp decline from mid-2014. As a result, Net Foreign Assets (proxied by Foreign Reserves minus External Debt in the absence of comprehensive and timely NIIP data) have declined sharply.

one hand, broad credit to the private sector in EM has increased from 70% of GDP in 2000 to 130% of GDP in 2015 (87% ex-China). Of this, about 20% of GDP represent external debt. On the other hand, EM foreign reserve growth slowed since 2011 and went into sharp decline from mid-2014. As a result, Net Foreign Assets (proxied by Foreign Reserves minus External Debt in the absence of comprehensive and timely NIIP data) have declined sharply.

Sharp Monetary Tightening: The above factors make Emerging Markets particularly vulnerable to a tightening in global monetary conditions. True, some leading central banks, the ECB and the BoJ most notably, maintain a staunchly accommodative stance, delving deeper into negative interest rate territory. At the same time, the Fed last week revised its interest rate projections from four hikes to two in 2016. Yet, this was  no more than a belated acknowledgement of reality and had already been well priced in by markets (which adjusted further downwards in response). What is more, it represents only a feeble counterforce to the tighter monetary conditions induced by the end of QE3. Economists at the Atlanta Federal Reserve estimated that this “tapering” was equivalent to nearly 300bps worth of rate hikes (“Shadow Federal Funds Rate”).

no more than a belated acknowledgement of reality and had already been well priced in by markets (which adjusted further downwards in response). What is more, it represents only a feeble counterforce to the tighter monetary conditions induced by the end of QE3. Economists at the Atlanta Federal Reserve estimated that this “tapering” was equivalent to nearly 300bps worth of rate hikes (“Shadow Federal Funds Rate”).

It is also important to remember that EM balance of payments surpluses have played an important role in sustaining the global liquidity expansion since early in the millennium, recycling accumulated reserves into US Treasury purchases. This was most sustained during the 2003-10 period when EM holdings approached 45% of total outstanding, far outstripping those of the Federal Reserve at less than 20% of GDP. These purchases turbocharged the earlier rounds of QE, but acted as a brake on QE3 when they reversed. Although a mere corollary of the reserve declines mentioned previously, the scale and change of direction of these figures provides another indication of the change in global monetary conditions and their reverberations through the financial system.

Bottom Line

In sum, arguments for a sustained rally in EM equities appear weak. The losses of the past years reflect not just a flippant change in sentiment, but a structural deterioration that will not turn on a dime. What is more, growth models in transition add another break to any recovery in the short term, while export sectors remain dependent on a more vigorous pick up in demand in DMs.

With the medium term outlook thus constrained, there could be short term opportunities. The recent stabilization in commodity prices (and sharp rally in oil prices) is certainly non-trivial for many EM exporters, without being severe enough to adversely impact commodity importers, be they developed-or emerging markets. But on the other hand, Fed Futures now price in between zero and one rate hike for 2016. To a large extent this reflects the dismal performance of US GDP growth expected for Q1. Once this data point is out of the way, there is a risk that market expectations will adjust abruptly to a new rate outlook, be it only to come in line with the Fed’s own forecast. As such, investors should fade short term rallies, rather than buy into them.